December 26, 2017

As 2017 will be closing its chapter in few days, and 2018 has many fraud and corruption scandals looming on the horizon, I contemplate the corporate of developing countries and the actual role of the board of directors in preventing and deterring corruption, money laundering, and financing terrorism. While my views in this article may look like a critique, they underscore severe flows that are permeating in most of these boards. I prefer to have my opinions be perceived as an expert advice directed to the board and its members.

Before I embark on delineating my viewpoints, I want to assert on the following points:

- Organizations, listed or unlisted, are social organs. An organization’s culture is affected by the country’s culture, values, and norms in which it operates.

- Prevalence of the rule of law differs from one country to another.

- The political will to fight corruption differs from one country to another.

- Prevalence of corruption and nepotism differs among these countries.

- There are different governance regimes in these countries.

- These countries have different poverty, illiteracy, and unemployment rates.

- Economic growth varies among these countries

- The economy of some of these countries is profoundly dependent on natural resources such as oil and gas.

- The majority of local investors in these countries are unsophisticated.

- In most of these countries, transparency, accountability, and integrity qualities in business dealings are poor.

- The true Independence and effectiveness of the judicial system in most of these countries is, at best, vulnerable.

- There are substantial doubts about the enforceability of court judgments in most of these countries.

- The competence and effectiveness of regulatory agencies monitoring organizations, listed and unlisted, business conduct is poor.

- The audit profession in most of these countries is at best inadequate and complicit in many countries.

Having stated that, I am aware of the environment in which the boards operate mainly in the Middle Eastern and African countries.

The board responsibility and its members’ rights and duties are primarily determined by the country’s corporate law. The board and its members must always make business and economic decisions in the best interest of the organization. For each decision, they should obtain and study all the relevant information diligently. However, board members should be competent enough to make informed decisions. But what determines the competency of a board member? A board member competency is met by fulfilling several corporate law requirements. Those requirements are beyond the scope of this article.

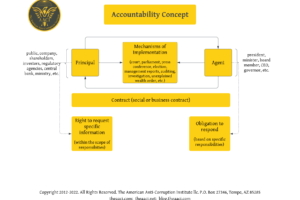

What I am concerned with is the board member’s anti-corruption intelligence. The American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI) coined the “anti-corruption intelligence” 1 term to determine ” the minimum, optimum knowledge a decision maker should have to avoid fraud and corruption intelligently. Such knowledge includes the proper blend of due diligence, internal controls, anti-corruption, governance, decision making, process auditing ( from a management perspective and duties) to avoid anti-corruption and fraud.” Financial and nonfinancial information live in both the pillars of the anti-corruption concept and each of the board decisions. The critical and common sense questions are: First, do the board members of corporations (listed and unlisted) of the Middle East and Africa possess anti-corruption intelligence? Second, are they required to have a reasonable financial and business competence?

The first question. Though I could not figure out reliable and independently published stats, I have substantial doubts that board members have proper and adequate anti-corruption intelligence. Based on first-hand experience and information, these boards, in most of the cases, do not have the appropriate knowledge about due diligence, internal controls, anti-corruption, governance, decision making, process auditing ( from a management perspective and duties) to avoid anti-corruption, fraud, money laundering, and fighting terrorism.

The second question. Each of these boards relies upon its accounting and management information systems in most of its business and economic decisions. In most, if not all, these countries, organizations use the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) to prepare and fairly present financial statements 2. The board should usually approve the audited financial statements before they are released. Again, the common sense says that a board member who approves the audited financial statements is presumed to know what the auditor’s report says and what the accompanying financial statements purport. Does he? Some of you may say, well, the board has an audit committee that handles the required financial and business expertise of the board. I do not believe that the audit committee waives the board members of their duties in this regard or their associated legal liability. Let me articulate on this question.

IAS 1 states that 3 “users are assumed to have a reasonable knowledge of business and economic activities and accounting and a willingness to study the information with reasonable diligence.” Even though users, referred to in IAS 1, indicates to external users of financial statements, I think that those who approve and oversee the financial reporting process should initially possess the presumed reasonable knowledge of the external users of financial statements. It seems to me that the answer to the second question becomes clear: the board members are required to have a reasonable knowledge of business and economic activities and accounting and a willingness to study the information with reasonable diligence. The anti-corruption intelligence concept includes such reasonable knowledge, as required by IAS 1. I am skeptical and have serious concerns about the board members competencies to meet the designated necessary reasonable knowledge. There are probably few organizations who are excellent and have adequate anti-corruption intelligence, but I believe they are not many.

Trying to avoid discussing the reasons underlying the boards’ anti-corruption illiteracy (accounting illiteracy included), I want to reiterate that the environment in which organizations do business have a significant bearing.

When the board members do not have adequate anti-corruption intelligence, and the board is dominated by one or two of its members, and the organization’s external culture characteristics are more or less as stated above, what would be the consequences? Though I have a short answer, let me list part of the considerable damages.

- The capital allocation will be inefficient and elusive

- The stock markets and exchanges will not function transparently and will not reflect the realities of the economy

- There will be much-untapped innovation and productivity

- Corruption, money laundering, and financing terrorism thrive

- Talents leave the country, as nepotism is the norm rather than the exception

- Quality of public goods and services deteriorates, and public trust in local products and services worsen

- Healthcare and educational services quality degenerate

- Board membership loses its substance. Individuals seek for the membership to gain a social status and probably some remuneration.

- Lack of foreign direct investment. Prudent investors will not invest in organizations governed by such boards! Even when a foreign investor is on the board, the risks at stakes are high.

Despite the gloomy board characteristics I discussed above, I have no doubts that there are boards whose members are smart, ethical, and honest. Chaired by educated, charismatic individuals, those boards are trying to do all that they can in the best interest of their organizations, communities, and countries. There are many organizations in the Middle East and Africa whose leaders are open to all that may help them meet their organizational and legal duties. I can see a new breed of visionary corporate leaders and entrepreneurs in the Middle East and Africa leading by example, having adequate anti-corruption intelligence, and instilling transparency, responsibility, and accountability in their daily routine business and economic decisions. I know many of them and proud to call them friends.

I sincerely believe that only board members who have adequate anti-corruption intelligence can make a difference in preventing and deterring corruption, money laundering, and financing terrorism. Reckless, careless, incompetent boards and board members will not. On the contrary, they pose serious, relevant socioeconomic and political risks.

Finally, I wish all boards and board members in the Middle East, Africa and the rest of developing countries happy new year.

Notes:

- The First Interview with Mr. L.b.Files, president of The AACI, October 3, 2017, http://bit.ly/2fTdqMB ↩

- The financial statements in this context are the general purpose financial statements as defined by IAS 1 or FASB. General purpose financial statements consist of 1- balance sheet, 2- income statement, 3- statement of changes in equity, 4- statement of cash flows, and 5- notes to the financial statements that are an integral part of these financial statements. ↩

- International Accounting Standards Board, International Financial Reporting Standards, IFRS, International Accounting Standard 1: Presentation of Financial Statements, Part A, par. 7, Page A292, 2010 ↩